The Kenya’s ASAL as opportunity for development

The arid and semi-arid lands (ASAL) of Kenya are among the poorest and most vulnerable regions of the world. The ASALs cover nearly 90% of the country’s land mass, are home to nearly 30% of its population and contain 70% of the national livestock herd (Ministry of Devolution and Planning, 2015).

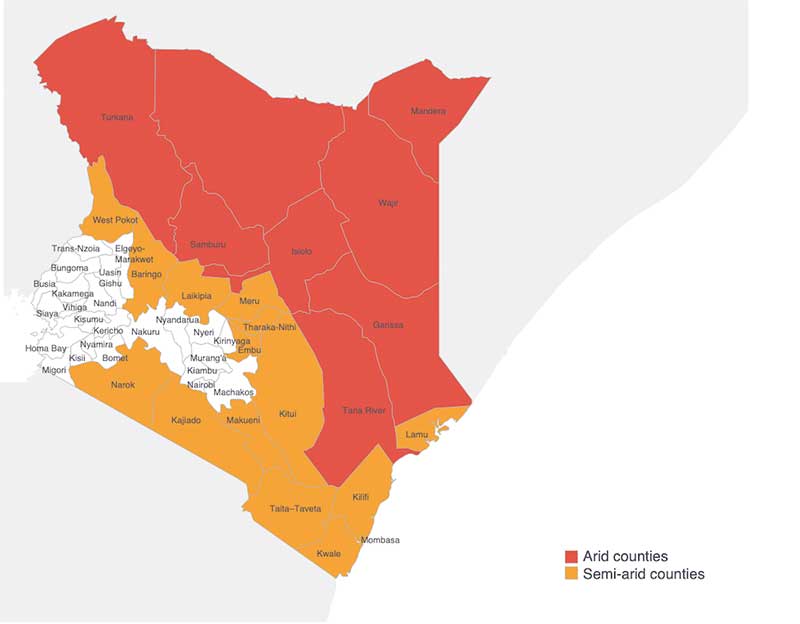

Kenya has 23 ASAL counties, 9 of them classified as arid and 14 as semi-arid.

In Kenya’s ASALs, drought is the most pervasive hazard, encountered by households on a widespread level.

Socioeconomic trends in ASALs areas partly reflect the negative impacts of extreme climatic events and droughts. In the Kenyan ASAL context, we observed socioeconomic trends associated with population growth and influx into ASALs, rapid sedentarisation of pastoral communities, changes in traditional land use and land tenure regimes, high levels of poverty, natural resource-based conflicts and changes in gender roles, among others.

More than three million pastoralist households are regularly hit by increasingly severe droughts, costing the economy an estimated $12.1bn between 2008 and 2011. For livelihoods that rely mainly on livestock, the high livestock mortality rate has devastating effects, rendering these pastoralists among the most vulnerable populations in Kenya. As the impacts of climate change unfold, the link between drought risk, vulnerability and poverty becomes significantly stronger.

These recurrent, intense and widespread droughts between 2010 and 2014, coupled with locust plagues, restrictions on pastoral mobility and desperate pastoralists cutting trees and grass for their herds, led to an environmental crisis that undermined livelihoods and threatened lives through food insecurity and conflict over natural resources (Masih et al., 2014; Wanyama, 2014; Cherono et al., 2017; Omolo, 2010).

In addition, despite ASAL are home to most of the country’s national parks (that are the foundation of its thriving wildlife tourism), they have historically been marginalized in terms of resource allocation, infrastructure development, social service delivery and economic transformation.

Whilst Kenya’s Asal are still prone to climatic shocks, have inadequate infrastructure and rank low on the human development index, they undoubtedly have great economic and development potential. From the lessons learnt in past development efforts in Asal, it is now evident that by fast-tracking and enhancing the consolidation and exploitation of development opportunities available in the region, we can help to unlock enormous untapped potential for national economic growth. Asal not only offer abundant natural resources but they are also strategically located for regional trade. For this reason, the government has taken bold measures to give special attention to the region based on its unique needs. Many policies and authorities that aim to end drought emergencies and build resilience have only been formed recently. The National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) was set up in 2011, and the country has only recently begun to adopt a more anticipatory and holistic approach to climate and disaster risk, with the National Climate Change Response Strategy developed in 2010. Both the Sector Plan for Drought Risk Management and Ending Drought Emergencies and the National Climate Change Action Plan were developed in 2013, and the National Adaptation Plan was established in 2016.

These policies and plans all feed into the Kenya Vision 2030 (Government of the Republic of Kenya, 2007), which commits to ending drought emergencies by 2022. The NDMA has a mandate to establish ‘mechanisms which ensure that drought does not result in emergencies and that the impacts of climate change are sufficiently mitigated’ (NDMA, 2017a). However, as outlined in Kenya’s Sector Plan for Drought Risk Management and Ending Drought Emergencies (2013–2017), ‘drought management in Kenya has continued to take a reactive, crisis management approach rather than an anticipatory and preventive risk management approach’, which in turn has led to an overreliance on emergency food aid (Government of the Republic of Kenya, 2013a: 20–21). Moreover, there is no central DRM agency or law, and disaster preparedness is piecemeal and fragmented across the country, with little corresponding action, allocation of resources, policy or preparedness for disasters other than drought (Development Initiatives, 2017).

To conclude, how the situation should be manage? And with which approachs the local and international agencies should work in these areas?

- The need to integrate conflict management into drought mitigation strategies in conflict-prone areas. Climate change impacts are likely to aggravate resource-based conflicts. For example, conflicts may well arise over scarce water and pasture. This is also true for long-term grazing management strategies in areas of shared resources, where neighbouring communities have to constantly maintain dialogue and negotiation to avoid conflicts over resources.

- Climate change impacts affect a wide area across borders, so effective drought risk management, currently based on a geographic and thematic focus, must embrace an ecosystem- wide approach that borders and boundaries often constrain.

- Facilitate access to control over and management of grazing and watering resources. This entails promotion and support of intra- and inter-community sharing and management of shared resources to enhance resilience to climatic shocks.

- Building community structures/institutions such as pastoralist associations greatly increases local capacity to manage droughts and respond to emergencies before external support arrives.

- Multi-stakeholder approaches to disaster management improve responses through increased funding and sharing of experiences and best practices in the management of drought cycle.

- Some emergency interventions have eroded community coping mechanisms by undermining the local economy of pastoralists. For instance, humanitarian interventions save lives but do not necessarily empower the recipients to carry out alternative livelihoods.

- Having in mind that often, programmes do not adequately address the inclusion of women, youth and vulnerable men – that is, they are failing to link activities with the needs of vulnerable groups in responding to the challenges of climate change.

Ph: Davide Lemmi